The Ministry of justice is quite a recent creation, as previous to the year 1892 there were as many jurisdictions as departments, and each department frequently tried cases concerning themselves either as defendants or plaintiffs. There were restrictions on their arbitrary powers, but these restrictions were often overridden by a powerful head of a department. The board in whose hands the decision of an appeal was supposed to lie were not strong enough to enforce any judgment affecting the department of a strong minister or against an influential nobleman. Besides the courts there existed what might be called the germ of a Ministry of Justice in the board named Lukkhun. This board dealt with cases which were not directly concerned with the departments and with any appeals which the departments were pleased to send to them. But they had no real power. The work of deciding cases was divided amongst different sets of officials. The actual recording of evidence was done by the Talakarn (or judges); the guilt or responsibility of the parties was decided on the records by the Lukkhun. The Pooprap, or officials, who were supposed to know the law, fixed the punishment or amount of judgment.

All judicial officials received only nominal salaries, and it can be well understood that chaos reigned supreme, and that justice was only likely to be done when money and influence were on the side of the plaintiff.

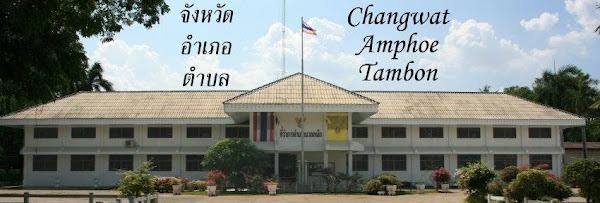

In the provinces the executive officers acted as judges, and could do pretty well as they pleased. In 1892 the Ministry of Justice was established, and all the judicial functions of the various departments, with the exception of the military

and naval courts and the palace court, were consolidated under the control of a Minister of Justice. This change was confined to Bangkok at first, but in 1895 all the central provinces were brought under the same control. The outlying provinces of Petchaboon, Udawn, Isarn, and parts of the Malay States still remain as before, but appeal from the courts in these districts are now forwarded to the Appeal Court at Bangkok. It is intended to incorporate the whole of the interior gradually, as time and money will permit.

At present every province is divided into Muangs with a District Court (San Muang) capable of trying cases up to five thousand ticals in value

and criminal cases involving punishment not exceeding ten years imprisonment. An appeal lies to the Circle Court (San Monthon), established in the capital of each province. This court is capable of dealing with every kind of case, both civil and criminal, and the cases from the District Court and those entered originally in the Circle Court are subject to appeal to Bangkok. The Bangkok Appeal Court is in two divisions, one of five judges dealing with appeals from the provinces, and one of three dealing with appeals from Bangkok and from the provinces not yet incorporated under this ministry.

A final appeal lies to His Majesty the King, who has delegated his duties to the tribunal composed of five members commissioned under the Royal Sign Manual. This tribunal may be termed the Supreme Court of Appeal (San Dika).

Friday, September 19, 2008

Judiciary system in 1904

After I wrote on the judiciary subdivision of the country, the corresponding section from The Kingdom of Siam: 1904 is interesting to compare, as it both describes the old system and the then newly established one.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment