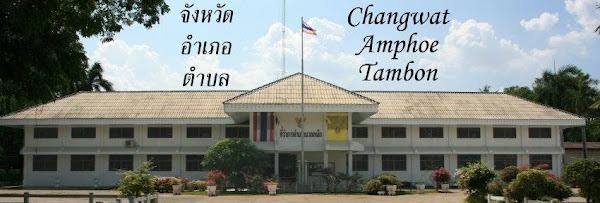

In this system, the district officer was the lowest level of generalist, and an important man. The district officer and his deputies became the chief source of higher administrative personnel in the tesapiban system. And it was at the level of the district that the official structure of government came into contact with the populace. From the beginning, the district officer was the local eyes and ears - and perhaps the nose - of the government, as well as the chief executive of a small domain, vested with symbols of authority in an authoritarian society. He was the king's man.Though the above quote is on the role of the district officer during the thesaphiban in the years 1892 to 1910, and taken from a 1966 book, it is basically still valid today. The leaders of the two lowest tiers of the central administration - village headmen and subdistrict headmen - are no career bureaucrats but elected local people, and it is the district officer who consults with these headmen on a regular basis. At the beginning of the 20th century (and for many parts of the country until much later) the difficulty of traveling or communicating made such a hierarchical system a necessity, as it was simply impossible for a villager to get into direct contact with the province administration.

William J. Siffin, The Thai Bureaucracry, page 88.

But of course, the district officer has much more to do than just being the middlemen between the populace and the province administration. Just recently, the Department of Provincial Administration (DOPA) has put a PDF with 294 pages on their website titled "กฎหมายที่เกี่ยวของกับ อํานาจหนาที่นายอําเภอ" (The laws which are related with the power of the district officer) - a wide collection from the Criminal Act, Family Registration Act, Weapons Act, Hotel Act, Fishery Act and many more laws covering a wide area of topics. Way too much to read for me, at least it is possible to copy-and-paste it into Google Translate...