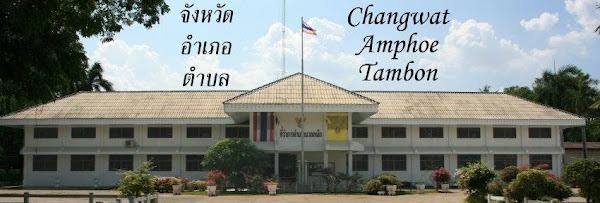

At the core of structural impediments to reform in Thailand lay the extraordinary degree of centralization. With the honourable exception of the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority, Thailand had no local government truly worthy of the name in 1997. While liberalism and pluralism were flourishing at the national level, out in the countryside provincial governors and other state officials continued to exercise an exceptional degree of political control. There were elected municipal and provincial councils, but these were weal bodies whose powers were tightly delimited by Bangkok ministries. The great majority of councils had been captured by construction contractors and other business interests. Crucially, moves to make the office of provincial governors an elected position were firmly resisted throughout the constitution-drafting process. As career bureaucrats in the Interior Ministry, sent out from the capital to administer in a quasi-colonial fashion, provincial governors were one of the largest obstacles to progressive change. Indeed, while Thailand's political order was undergoing extensive reform during the second half of the 1990s, the officials in numerous provinces were building themselves immense new salakan changwat (provincial halls) at vast expense. These monumental structures symbolized their determination to resist the forces of decentralization at literally any cost. [...]

Friday, October 28, 2011

Decentralization at the 1997 constitution

In the 2002 book "Reforming Thai politics", edited by Duncan McCargo containing 16 chapters by different scholars in Thai studies, I found a very interesting paragraph on the decentralization with the 1997 constitution in the introduction chapter. I have only read the introduction of the book so far, but want to share this quote already now.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment